Photos from South Africa

| Home | About | Guestbook | Contact |

SOUTH AFRICA - 1970-1975

A short history of South Africa

The Republic of South Africa is the southernmost country in Africa, with a very diverse population of around 60 million people. Black South Africans comprise about 81% of the population; the two most spoken first languages are Zulu, around 23%, and Xhosa, with 16.0%. Afrikaans, a language developed from Dutch, is the first language of most Coloured (mixed race) people and White South Africans, with 13.5%, while people of European and Asian ancestry speak English (almost 10%); it is also the language of commerce and international affairs. South Africa has 11 official languages: in addition to those first four most spoken languages, the other African languages are Sotho, Tswana, Swazi, Pedi (Northern Sotho), Ndebele, Tsonga and Venda.

Fossil finds indicate that hominid species have lived here as long as three million years, starting with Australopithecus africanus, discovered in subterranean caves about 50 kilometres northwest of Johannesburg - now named “The Cradle of Humankind”. Modern humans (Homo sapiens) have inhabited Southern Africa for at least 170,000 years. The Khoisan (Khoe-Sān) peoples were the only indigenous people who lived here before Bantu-speaking peoples settled in the north of present-day South Africa by the 4th or 5th century CE. These were the pastoralist Khoekhoen, formerly known as “Hottentots”, a term given by Dutch settlers, referring to the click consonants in their language. The San (a Khoekhoe word meaning “forager”) were hunter-gatherers and were called “Bushmen” by white settlers. They are the first cultures of southern Africa; cave paintings have been found in all countries in the region. Their descendants refer to themselves by their distinct individual groups.

Bantu-speaking people, who used iron, practised agriculture and had cattle herds, slowly expanded south from about the 5th century CE. They gradually displaced and mixed with the Khoisan speakers; the present-day Sotho, Xhosa, Zulu and Swazi languages contain click consonants, adopted from the original inhabitants. There are indications that iron implements found in KwaZulu-Natal date from the 11th century. The Xhosa-speaking people reached the furthest south, to the Fish River, about halfway between present-day East London and Port Elizabeth (Gqeberha). Further north, the Zulu-speaking peoples had settled, and these two were the main Bantu groups at the time of European contact.

The Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias was the first European to land in southern Africa, on the west coast in Walvis Bay (Namibia) in 1487. He continued partway along the eastern coast and, on the way back, saw a cape he named Cabo das Tormentas (‘Cape of Storms’). It was renamed Cabo da Boa Esperança (‘Cape of Good Hope’) by King João II of Portugal: it was the gateway to the riches of the East Indies. By the early 17th century, English and Dutch merchants had gradually ousted the Portuguese from the trade in spices and sometimes called at the Cape to get provisions. In 1647 two Dutch sailors were shipwrecked here and stayed for several months; they could get drinking water and meat from the natives and grew vegetables. Back in Holland, they reported that it would be an excellent place to make a garden and warehouse to supply passing ships on their way to the Indies.

In 1652 the Dutch established a supply station for ships of the Dutch East India Company at what would become Cape Town. This small settlement grew when former employees stayed on after their contracts were finished - “vrijlieden” or “vrijburgers” (‘free citizens’). The Dutch traded with the Khoisan (Khoe-Sān) peoples but tensions soon developed when they found that white farmers now occupied their grazing land. It escalated into two wars between the two groups, the Khoikhoi-Dutch Wars in the last half of the 17th century, which led to the Khoisan’s disappearance from their ancestral lands.

Dutch traders also brought in slaves from the East Indies, eastern Africa and Madagascar. In time, liaisons between those various peoples led to a distinct ethnic group, the Cape Coloureds, speaking the Dutch language of the time, that evolved into present-day Afrikaans. The colony grew with Dutch, German, Huguenot and Irish immigrants, and Dutch colonists expanded eastwards until they reached the Great Fish River and came into contact with southwesterly migrating Xhosa. The Dutch “vrijburgers” had become independent farmers and were known as “Boer” - the Dutch word for farmer. Some adopted a nomadic lifestyle and were known as “Trekboer”. They formed militias and made alliances with local Khoisan peoples to repel raids by the Xhosa. It led to three wars between the Boer frontiersmen and the Xhosa between 1779 and 1803.

In 1795 the Dutch Republic was occupied by the French, who proclaimed it the “Batavian Republic”. Britain was at war with France and sent an expedition to the Cape to occupy the territory; after a short battle, the British took control. In 1803, the British returned the Cape Colony back to the Batavian Republic upon cessation of hostilities with France. But after one year, peace was broken, and Britain occupied the Cape again on 8 January 1806 after a small battle. Eight years later, the Dutch government formally ceded sovereignty over the Cape to the British. There were six more wars between the Xhosa kingdom and the British between 1811 and 1879. These were also known as the “Kaffir Wars” - “Kaffir" being a term derived from the Arabic kāfir, meaning “nonbeliever”, a term used by Arab traders for non-Muslim people. The word was passed on by the Portuguese. But in South Africa, it has become a very offensive, derogatory racial slur.

From the early 1800s, many Dutch settlers had departed the Cape Colony to be free of British rule; the British had declared English the only language, and the use of Dutch was forbidden in the colony. There were disputes about settlers’ claims when slavery was abolished in 1834, and the authorities were also opposed to the Boers’ unduly harsh treatment of the indigenous peoples. During the 1830s and 1840s, large groups of Boers moved north by wagon trains: The “Great Trek”. They called themselves “Voortrekkers” (pioneers or pathfinders) and eventually founded several autonomous Boer republics after conflicts with the African peoples already living there.

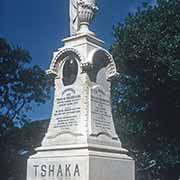

The most prominent of those peoples were the Zulu, initially a small clan of the Nguni people, whose leader, Shaka kaSenzangakhona, reorganised the military, making his “impis” a formidable force. Between 1818 and 1820, the Zulu Kingdom’s military campaigns overran the area. The British established a small settlement in 1835 on the coast of what the Portuguese had called Natália, in Port Natal; this settlement became the town of Durban. Meanwhile, Boer “Voortrekkers” had trekked across Drakensberg passes and arrived in Port Natal in 1837. Their leader, Piet Retief, signed a deed of cession with Dingane, Shaka’s successor, on 4 February 1838, but two days later, almost all Boers were killed by the Zulus. On 16 December that year, the Boers were victorious at the Battle of Blood River - they killed thousands of Zulus. They then founded the Republic of Natalia the following year, but this was annexed by the British in 1843, forming the Colony of Natal.

In 1879 the British invaded Zululand after an ultimatum they had presented to Cetshwayo, their king, in which the Zulus were ordered to disarm and pay reparations for alleged “insults”, had been rejected. They camped at Isandhlwana and, on 22 January, were attacked by a force of 20,000 warriors who completely overwhelmed them. It was a stunning victory followed by an attack on Rorke’s Drift mission station, ending when the Zulus withdrew the following day. On 4 July 1879, the British invaded Cetshwayo’s capital Ulundi, and the following battle broke the Zulu nation’s military power. Zululand was absorbed into the Colony of Natal.

Most Voortrekkers had left Natal when it came under British rule and in 1854 established the Orange Free State, an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty. In 1852 they had established the South African (or Transvaal) Republic in the north, a large area north of the Vaal river, comprising all or most of the present provinces of Gauteng, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North West. It was recognised by the British, but relations deteriorated when the British Cape Colony expanded into its interior, leading to the First Boer War in 1880-1881. It was won by the Boers, using guerrilla warfare tactics, but in 1899 war broke out again, and the Second Boer War (1899-1902) ended with the end of the South African Republic and the Orange Free State as independent countries. During the war, the British used concentration camps where women and children were held without adequate food or medical care. Almost 4,200 women and over 22,000 children under 16 died in those camps.

On 31 May 1910, the Union of South Africa was created of the Cape, Transvaal and Natal colonies and the Orange Free State Republic. It was a British dominion and nominally independent. Three years later, the Natives’ Land Act severely restricted land ownership by blacks; they controlled only seven per cent. The union became fully sovereign from the United Kingdom in 1931, and in 1948 the National Party, an Afrikaner nationalist party, came to power. It strengthened racial segregation and classified all peoples into races: Whites, Blacks, Coloureds (mixed-race people) and Indians. Each had separate rights and limitations, with the whites, only 20% of the total, on top. This legal segregation became known by the Afrikaner (Dutch) term “Apartheid”: the African majority was disadvantaged in every respect: jobs, income, education, housing and living standards.

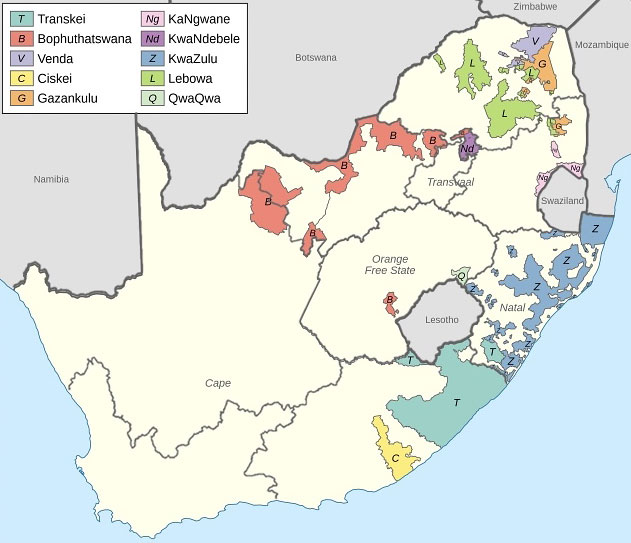

Already in 1954, the ideas of “Grand Apartheid” had led to the adoption of measures like the Group Areas Acts and the Natives Resettlement Act, that would create separate Bantu “Homelands” that would then lead to a white majority in the rest of the country. The homelands, often called “Bantustans”, would eventually be made independent so that the blacks would lose South African citizenship. Each ethnic group would have its own state, and people of that ethnicity would be forced to locate to that “homeland” where they would have full rights under their own government, even if they had never been there before. It was presented as “Separate Development”, an enlightened policy. Yet, its effect would be that black South Africans, even if they lived in “white” areas where they worked, would, as “citizens” of those homelands, lose the few rights they had.

On 31 May 1961, South Africa became a republic; a referendum, only open to whites, had narrowly been won - Natal, with a majority of English speakers, had voted against it. The government stepped up the policy of separate homelands: in 1963, Transkei, a reasonably large area inhabited by Xhosa-speaking peoples in the northeast of the Cape province, attained self-government and was nominally declared independent in 1976. It was slightly larger than Lesotho to its north and could have been a viable state. But, being a product of Apartheid South Africa, the rest of the world never recognised it. A year later, Bophuthatswana, a “homeland” for the Tswana people, was declared independent; but this was a scattered patchwork of enclaves spread across Cape Province, Orange Free State and Transvaal. The other eight “homelands” were just as unviable.

There was opposition to these policies both within and outside the country, and security forces cracked down on anti-apartheid organisations, like the ANC (African National Congress), Azanian People’s Organisation and Pan-Africanist Congress. As far back as 1950, Nelson Mandela was elected President of the ANC and was many times arrested for his activities against racist policies. He was tried in 1964 and sent to Robben Island, a prison island off the coast near Cape Town, where he stayed until 1982. Meanwhile, violence and dissent only grew, and South Africa became more and more isolated. Eventually, under the presidency of F.W. de Klerk, the National Party lifted the ban on the ANC and other political organisations. It released Nelson Mandela from prison after 27 years of serving a sentence for sabotage. In 1994 South Africa held its first universal election, and the ANC won by a vast majority. Nelson Mandela became President of a new South Africa: the first black chief executive. He saw national reconciliation as the primary task of his presidency and appointed de Klerk as Deputy President to reassure the white population.

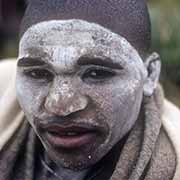

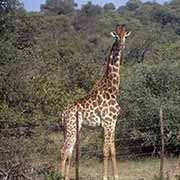

The ANC has been in power ever since, and although many black South Africans have become members of the middle and upper classes, there is still poverty. Corruption has been a problem, especially under Jacob Zuma, President between 2009 and 2018). But South Africa is once more respected by the outside world, aiming to be, in Mandela’s words, a multicultural “Rainbow Nation”. It is a beautiful country with spectacular scenery, wildlife sanctuaries, architecture and cultural attractions. The photos on these pages were taken between 1970 and 1975 when Apartheid was still the law of the land. Happily, a lot will have changed since then! The following map shows the areas of the Bantustans as they were when I took the photos on these pages. The map is courtesy of wikimedia. I added the present provincial borders.